Unlocking Mainframe Data: From Legacy Systems to Analytics in Databricks

Mainframe technology has always been intriguing but has largely been a mystery to me how it worked or what ‘mainframe’ even meant.

Working at Plains, many of our commercial applications for crude oil accounting, scheduling, volumetric data (noms and actuals) and contract capture all run largely on the mainframe. Over the past few months, I have had the opportunity to learn from and work with a few mainframe developers and SMEs on the commercial side of our business.

As mentioned above, my biggest challenge learning all of this was that I did not really understand what mainframe meant. So, to get my hands dirty, I leveraged some open-source technology to spin up an extremely barebones mainframe on my computer to get a feel for various mainframe concepts.

In this post, I’ll walk through what a mainframe is, how I emulated one, and how data moves from mainframe to Databricks. I hope this post demystifies some mainframe concepts for you!

What is Mainframe?

Talking with friends in other industries, mainframes are still very much the backbone of enterprise computing for industries like banking, airlines, and energy, where transaction integrity and speed are critical. Several IBM studies indicate the continued use of mainframes is widespread and will continue well into the future.

Mainframes handle almost 70% of the world’s production IT workloads, according to one of the studies.

Mainframes are enterprise data servers engineered to handle massive, mission-critical workloads, and it is not uncommon for them to process transactions in the trillions per second. They are built to run the world’s most important data systems without interruption, even under extreme load.

The term mainframe initially referred to the large cabinet or ‘main frame’ that held the central processing unit (CPU) of early computer systems.

Relevance to Plains

The role I have at Plains has inspired me to get hands-on with mainframe technologies since many of our commercial applications run on an IBM z/Architecture (or something very similar). With my role focused on data engineering/ML, getting data out of mainframe into our Lakehouse is critical.

To have more informed conversations with that team, I wanted to get hands-on with the technology. I am a big believer in learning by doing.

After a bunch of research, I found an open-source software implementation of the mainframe System/370 and ESA/390 architectures, in addition to the latest 64-bit z/Architecture. While infinitely less complex than the mainframe environment we have at Plains, it has still allowed me to get my hands dirty with some mainframe concepts. I also validated the environment with our internal mainframe team to make sure I was on the right track with my learning.

The software is called Hercules, and it has been incredibly helpful to wrap my brain around mainframe technology.

Getting Hands-On with Mainframe

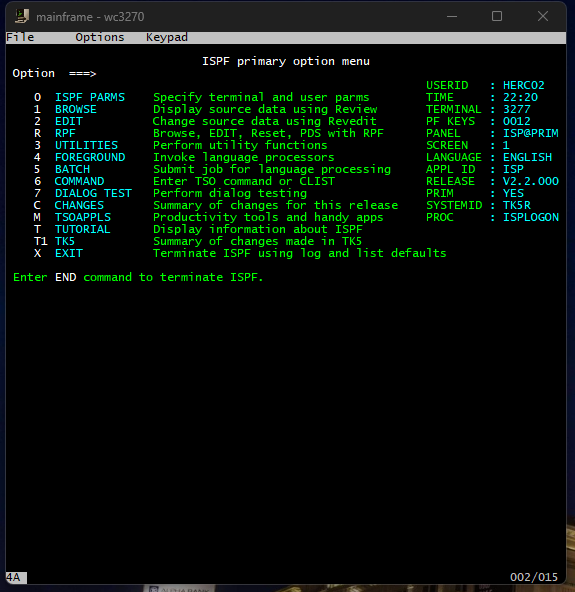

To be honest, I had not even really seen what a mainframe looked like prior to experimenting with this emulator, so this was a fun experience. After logging in, you are greeted with what is called an Interactive System Productivity Facility (ISPF) menu that provides a way to interact with the mainframe.

There are a wide variety of options here, most of which I have not touched. Most of my time has been spent in the UTILITIES option. Selecting option 3 will take us there.

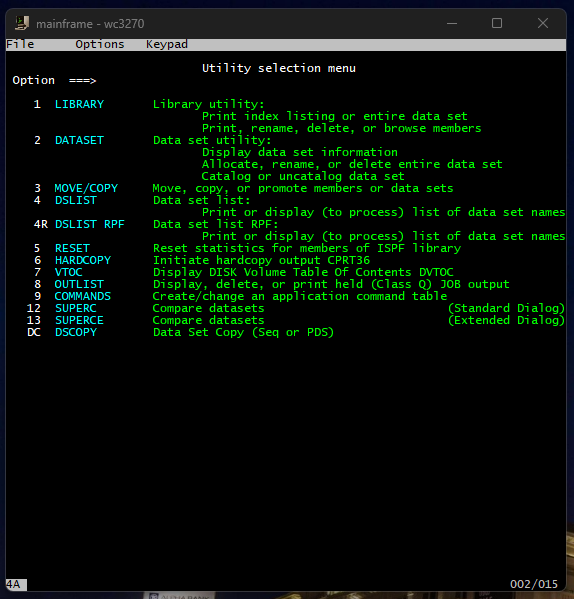

From there, we have several more options to choose from. I really wanted to get hands-on with some COBOL programming, so I spent most of my time there.

Once inside the Utilities menu, I quickly discovered that everything in the mainframe world revolves around datasets. These are essentially the mainframe’s version of files, but they’re far more structured and rigid.

- Some datasets behave like simple text files.

- Others act more like folders, holding multiple “members” such as JCL scripts, COBOL programs, or configuration files.

JCL (Job Control Language) was cool to learn about, and it is basically an instruction sheet that tells the mainframe what work to do. A JCL script defines:

- Which datasets to read from

- Which programs to run

- Where to put the output

- What system resources to allocate

When you submit a job, the mainframe reads your JCL, locates the datasets you reference, runs the COBOL program you point to, and routes the output into spool datasets that you can view through SDSF (System Display and Search Facility) or another similar job log viewer.

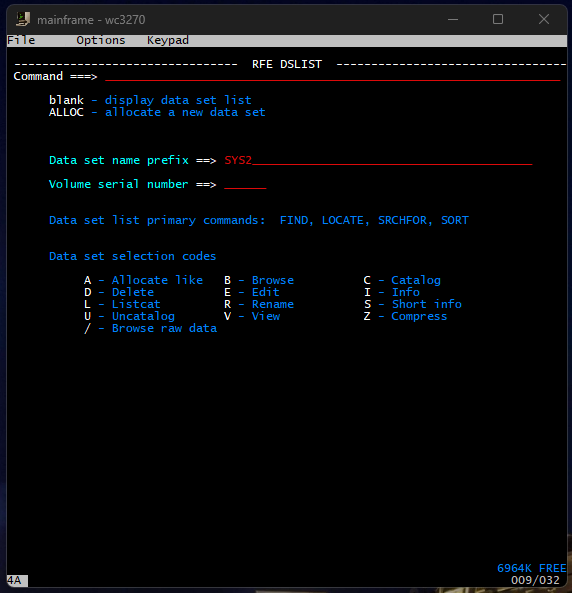

Selecting option 4 or DSLIST allows me to search for the dataset I want. In this case, I am searching SYS2, which is used for datasets that belong to the operating system, utilities, or shared components, not to individual users.

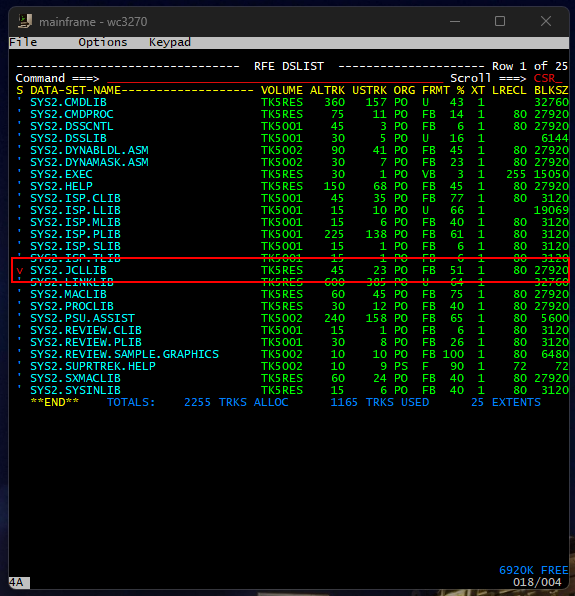

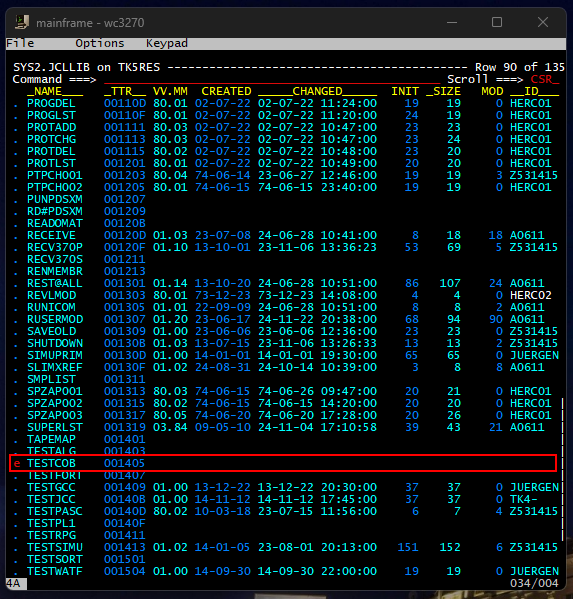

This emulator I have loaded has lots of prebuilt COBOL scripts that I can experiment with to get a feel for how it works. All those examples are contained within the dataset SYS2.JCLLIB. Pressing enter brings up the following screen where I can select my dataset by using the arrow keys and entering V to view the contents.

After pressing enter, we are brought to another screen where we can see a variety of different things, COBOL scripts being one of them. I stumbled upon a basic ‘Hello World’ application in COBOL to familiarize myself with the syntax and get a feel for submitting jobs on mainframe.

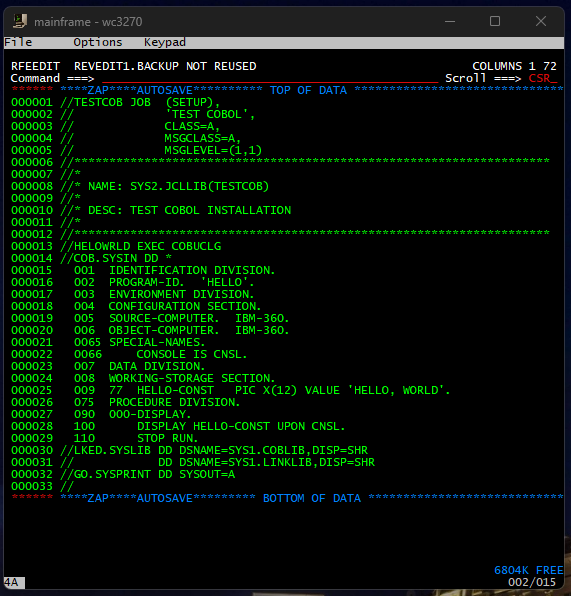

Scrolling down to that file and entering E allows us to view the syntax of that COBOL application.

This COBOL script just prints Hello World. We can submit this job by entering the submit command in the Command prompt.

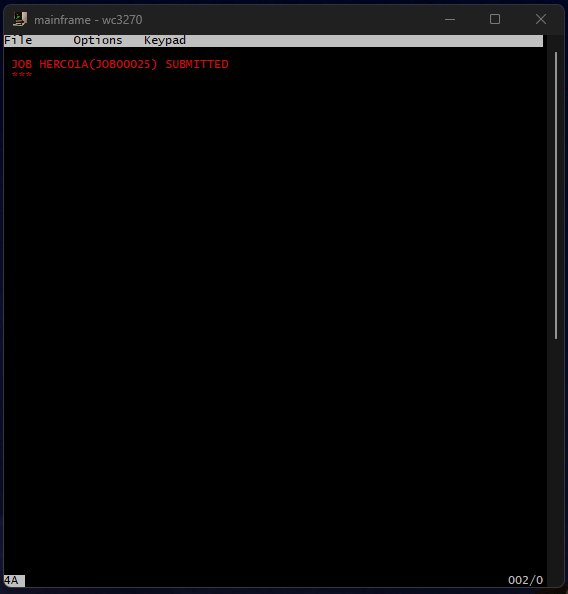

Doing so returns this:

I was trying to identify where I could see the output of this job, but could not figure it out 😂

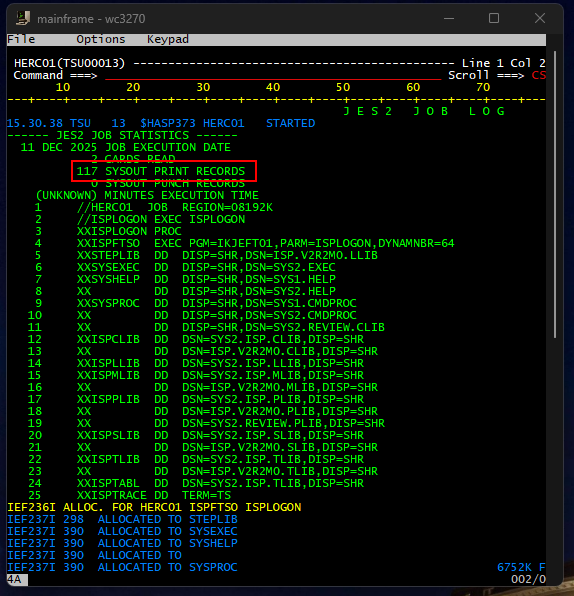

Talking with the mainframe team at Plains, they leverage a tool called System Display and Search Facility (SDSF) to monitor, manage, and view system activity, job queues, and job output in real-time. I do not have access to that on my emulator, and when I tried to view the logs in the OUTLIST utility, which basically displays JOB output, I could not find it.

I can see there is something called SYSOUT where printed records are stored, but I could not figure out how to access that. In theory, I should have been able to view the ‘Hello World’ output there.

Extracting Data from Mainframe

One of the most important aspects of mainframe systems is their use of specialized databases. Unlike modern relational databases, many mainframe databases such as IBM’s IMS (Information Management System) are hierarchical in structure. This means data is organized in a tree-like format, with parent and child records, rather than tables with rows and columns. I have yet to dig into these databases at Plains but I hope to in the coming months.

As things stand now (and as far as I understand), we are leveraging scheduled jobs via JCL that call mostly COBOL code on mainframe. These jobs export data from various commercial apps that run on mainframe, into a tilde separated format. These tilde separated files are often times SFTP’d between file shares for consumption.

There are also .NET client applications built for deal capture that leverage a SQL database where data is copied from mainframe into these client SQL databases on a scheduled basis.

We are tying into a mix of the tilde separated files and the client app SQL servers to pull volumetric, deal information, and lease supply data and using Data Weaver to ingest and process this data in Databricks.

While we are not connecting directly into the mainframe IMS databases today, depending on our end users requirements, we may need to explore that to pull that data on a more regular interval.

I suspect this will not be a problem for now since the jobs on mainframe to extract the data are scheduled to run in accordance with crude oil accounting requirements and operational workdays. In a midstream context, a “workday” is not a calendar day, but a contract-defined 24-hour operating period used for measurement, allocation, inventory reconciliation, and settlement.

Aligning extract jobs to these workday boundaries ensures that volumetric data, deal activity, and lease-level movements remain consistent with how the business measures and settles crude. As long as downstream ingestion and processing remain in sync with these accounting cutoffs, the data we land in Databricks should reconcile cleanly with commercial and accounting systems, even if the underlying source systems and technologies differ significantly.

Conclusion

I had fun trying to get all this running on my laptop and I learned a ton in the process. What the mainframe has done and is doing at Plains is amazing, and I am excited to see what data and information we can unlock out of the commercial apps that run on the IBM mainframe using some cutting edge technology in Databricks.

I hope those that have not interacted with a mainframe (like me) found this blog helpful. I am excited to continue working with the team at Plains to learn more about this technology.

Thanks for reading! 😀