🤖💬 A Conceptual Guide to MCP

I feel a bit late to the game on this but better late than never! I have been seeing lots of people talk about the Model Context Protocol (MCP) online and I thought it would be good to write a blog post on it while I try and wrap my head around what it is exactly.

I generally approach these types of things skeptically since there is lots of hype in the AI industry right now. I find myself getting less and less excited about new LLM releases or new agent frameworks coming out as it is incredibly easy to get lost in the hype that could potentially lead us down a rabbit hole.

I think it is much better to pick a framework and LLM, stick with it, and really nail down your data, software, and platform engineering practices to build amazing GenAI applications.

With all that said, the reason MCP caught my eye is it reminded me of web services standardizing on REST and how easy it is to now connect into and pull data from different applications.

MCP seems to be a start to standardize on how LLMs communicate with external systems.

Sounds pretty good, but how does this work?

In this blog, lets explore MCP and see if all the hype around it is justified.

🤷♂️ What is MCP?

Like I mentioned in the introduction, MCP is basically a standardized way for LLMs to connect with external tools and data sources. On the surface, this seems like much needed standardization.

LLMs by themselves cannot interact with anything external to the data they were trained on. This is where tool calling and agents came into the mix promising developers a pattern where you could have an LLM interact with an external tool, like sending an email on your behalf.

For anyone who has tried building agentic applications, you know how frustrating it is to build a reliable integration with one external system, and scaling that to multiple external systems gets even more difficult. Just like the tech industry standardized on REST for interacting with API’s, MCP seems to provide a standard way for LLMs to interact with the outside world. Developers generally like standards and just like how REST APIs have made many of our lives as developers easier, MCP promises to do the same for enabling LLMs to interact with the outside world.

MCP breaks down into the following high-level architectural components:

-

MCP Hosts: Applications like developer IDEs, or AI-powered tools that initiate requests to access data or services via the MCP protocol.

-

MCP Clients: Components that manage one-to-one communication channels between the host and an MCP server, acting as the bridge for protocol execution.

-

MCP Servers: Lightweight services that expose specific functionality such as file access or API calls through the standardized Model Context Protocol interface.

-

Local Data Sources: Files, databases, and services on your own machine that MCP servers can access securely, enabling private, on-device interactions.

-

Remote Services: External APIs and cloud-based systems that MCP servers can connect to, making it possible to integrate with third-party platforms across the internet.

The idea behind this pattern is there would become a growing number of pre-built integrations you can tie your LLM into and the developer maintaining these MCP servers would be following best practices around secure software development principles.

🐙 GitHub MCP Server Example

To explain MCP in a more concrete example, I found a great example in the GitHub MCP Server repo that enables LLMs to interact with GitHub. This was a very timely example to find since I was just doing some work with Dagger on building out an AI agent that could leave comments on PR’s in GitHub based on the agents analysis of a Terraform Plan (you can check that out here if you are interested).

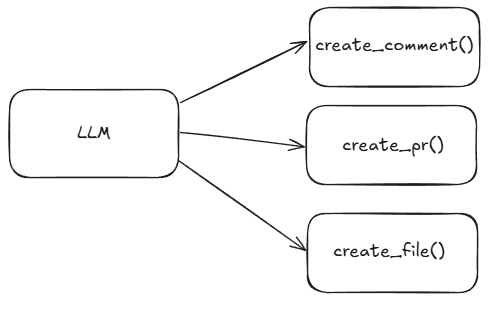

The diagram below demonstrates how I would traditionally implement an agentic application with tools, in this case, to interact with GitHub.

At a high-level, the above diagram articulates what seems like a simple amount of development, however, as you dig into implementing the above the complexity slowly starts to grow.

🧠 Tool Calling: Where the Simplicity Ends

At a glance, you’re just having an LLM trigger functions, but here’s what you really have to think about:

-

🔐 Authentication & Authorization

LLM ≠ User Identity: The LLM needs to act on behalf of a user. In the GitHub example, does it use OAuth tokens? GitHub Apps? PATs (Personal Access Tokens)?

Token Scope Management: If your tool needs to make changes (like create_file), how do you ensure it has just enough permissions?

Agent Identity: What happens when multiple users are using the same agent? Token/session management becomes non-trivial.

-

🧩 Function Design and Interface Schema

LLMs don’t call arbitrary code. They need to understand the inputs/outputs of each tool.

You need to define each function with:

Clear, constrained input schema (ideally JSON Schema or a Pydantic model)

Robust output expectations

You’ll also want to validate inputs before making real API calls.

-

🤖 LLM Reliability & Output Parsing

LLMs might:

Hallucinate function names or parameters.

Forget to call tools when needed.

Return ambiguous results if the function doesn’t give instant feedback.

You often need a loop where the LLM reflects on prior tool output and decides the next action.

-

🔁 Tool Execution Lifecycle

How do you structure:

State: Does the LLM remember what it already tried?

Retries: What happens when create_pr() fails due to merge conflicts?

Side Effects: Tools like create_file() may have lasting consequences. How do you sandbox them?

-

🕵️ Security & Auditing

Every tool call is essentially a privileged action. You need:

Logging and observability on what the LLM is doing.

Rate limiting and throttling to avoid accidental overload.

Guardrails for prompt injection or adversarial inputs.

-

🌐 Latency & API Complexity

Tool calls often involve remote APIs (e.g., GitHub), which:

Can be slow or rate-limited.

Might return unexpected errors or inconsistent schemas.

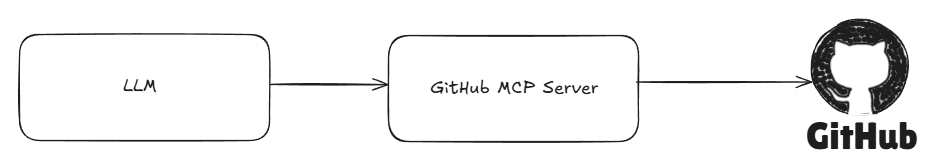

💡 GitHub MCP Server to the Rescue?

That’s why the GitHub MCP Server is so interesting. It acts as a middleware layer between LLM and GitHub, and seems to abstract:

- Token handling

- API consistency

- Permissioning

- Function schema

This could simplify development heavily allowing you to focus on the intent of the agent versus the low-level auth/config logic.

I am looking forward to getting the GitHub MCP server hosted locally in Docker to see if it could help streamline the Dagger agent I mentioned earlier.

🔐 Security Concerns

MCP is not without its potential risks. To understand what the risks may be we have to understand who creates and maintains MCP servers. Many of these MCP servers are open source and maintained by a variety of contributors. It also seems currently that the MCP specification requires developers to write their own authentication server. What this means is we must trust that the developers writing these MCP servers are following best practices when it comes to authentication and authorization.

These are not new problems. Foundations like OWASP have very well published standards on things like their authentication and authorization guidelines that developers can leverage to make sure they are following best practices when implementing their MCP server.

While we are on the topic of OWASP, they also have standards published around securing LLM related applications (I have a blog detailing some of those standards here).

I imagine that MCP implementations may be subject to the same LLM related vulnerabilities detailed in the OWASP standards. I found an interesting repository called the The Damn Vulnerable MCP Server (DVMCP).

This reminds me a ton of the OWASP Juice Shop which is an intentionally insecure web application that I have leveraged in the past to learn about cybersecurity for web applications.

DVMCP even has challenges to orchestrate certain attacks against their vulnerable MCP server that seem to align really well to the OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications. For example, they have one on tool poisoning.

This is a great resource for MCP server developers to understand some of the potential security risks associated with building out their implementation.

At the end of the day, MCP’s will have the same potential security issues any other software will have. Developers need to be thoughtful in their implementations and work to mitigate potential risks.

🎉 Conclusion

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a promising step toward bringing standardization and structure to how LLMs interface with the external world. This is something that’s sorely needed as GenAI applications become more complex and widespread. By offering a consistent pattern for connecting to both local and remote systems, MCP has the potential to significantly reduce the friction developers face when building agentic applications.

That said, there are still things to watch out for. Security, trust, and maturity of implementations are key factors that need to be addressed before MCP can be broadly adopted in production environments. The emergence of tools like the GitHub MCP server and the Damn Vulnerable MCP Server project show a growing ecosystem and community interest, which is always a good sign.

If you’re a developer working on LLM-based agents, MCP is absolutely worth exploring. It might just be the missing glue between your models and the outside world. But, as always, keep your security hat on and be mindful of how much you trust the servers you’re connecting to.

I’m looking forward to experimenting more with MCP in the wild and seeing how the ecosystem evolves.

If you’re working with MCP or building MCP servers, let’s connect!

Thanks for reading 😀